Hi! Thanks for subscribing. I thought I’d start this newsletter by sharing some research and writing from last year. In the future, I’ll also be sharing work in progress along with thoughts about illustration, ecology and growing thing, as well as anything else that feels relevant. These first few posts will be pretty regular and then will become more sporadic from that point forward.

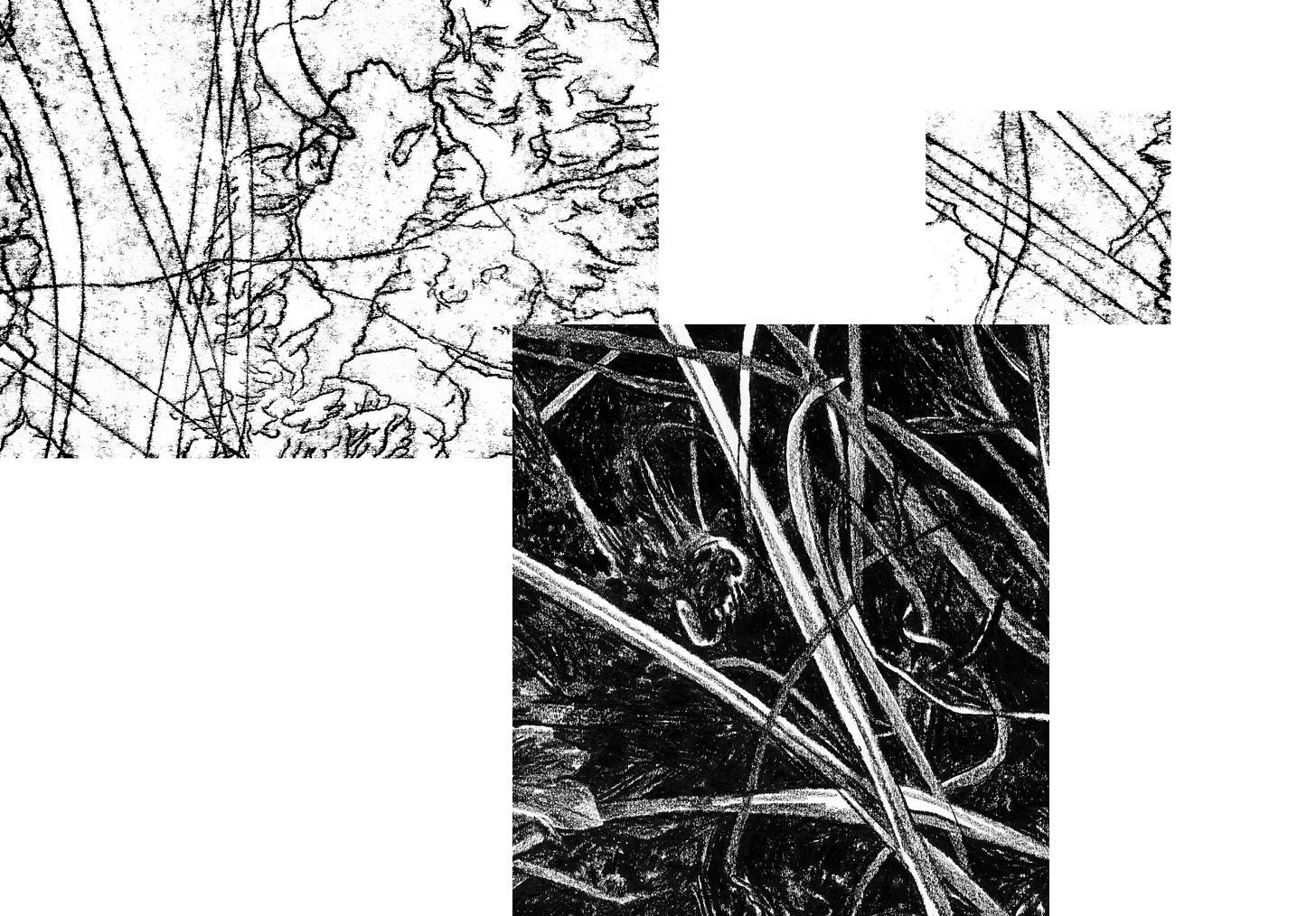

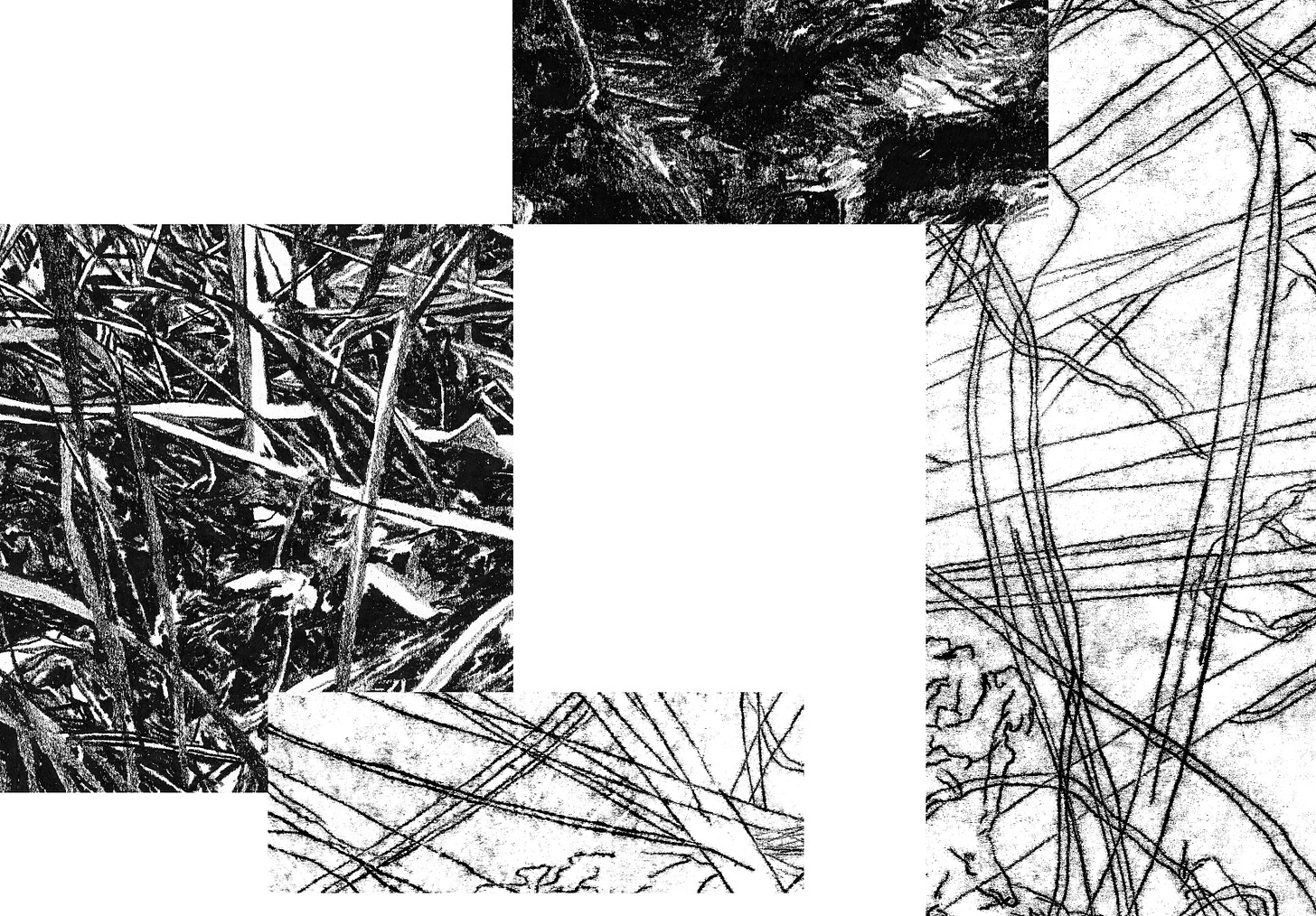

The following is taken from a presentation delivered in 2022 at ICON11 titled Twists and Loops: Illustrating Ecologically. The aim of the talk was to reflect on the inputs and development of A Piece of Turf, a collection of drawings and prints produced in response to observations of a small patch of weeds. This work was brought together into a publication and exhibition alongside prose by Beatrice Karol.

Ecological Complexity

What I aim to do is not so much learn the names of the shreds of creation that flourish in this valley, but to keep myself open to their meanings, which is to try to impress myself at all times with the fullest possible force of their very reality. I want to have things as multiply and intricately as possible present and visible in my mind. Then I might be able to sit on the hill by the burnt books where the starlings fly over, and see not only the starlings, the grass field, the quarried rock, the viney woods, Hollins Pond, and the mountains beyond, but also, and simultaneously, feathers’ barbs, springtails in the soil, crystal in the rock, chloroplasts streaming, rotifiers pulsing, and the shape of the air in the pines.1

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Complexity is at the very core of contemporary ecology. Processes, relationships, interactions and systems are the very way in which things exist. Things are not just unconscious lumps, decorated with accidents2 but twisting and looping, muddled and imperfect, fecund and specific. Dillard’s writing captures this sense intricately; rather than an attempt to catalogue and learn names and species the aim is to remain open to the multitude, to see things at multiple and non-human scales.

Scales

This notion of seeing at different scales is central to ecologist and philosopher Timothy Morton’s position, defining ecology as ‘...the thinking of beings on a number of different scales, none of which has priority over the other.’3. This scaling can, at first, feel disorienting. We are used to seeing and experiencing things at human-scales, but thinking ecologically means thinking at, and beyond, micro and macro scales (microbe, ecosystem, biosphere, DNA) both physically and temporally (era, anthropocene, geological, goldfish-time).

Each scale is bristling with activity and detail and, as we start to recognise this, we also become aware of the strangeness of this observation. As Morton says, we experience a ‘weird openness’4 that questions our assumptions about the relationship between ‘parts’ and ‘wholes’. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. Is it? This scaling-way-of-seeing shows me the massive finitude of parts, pieces and particles that make up ‘me’, whirling, bumping into each other, decaying, dying and reproducing inside me. The seemingly familiar entity starts to become less familiar, less known, uncanny in its closeness. For Morton, this scaled ecological view of the world, demonstrates that, ‘the whole is always weirdly less than the sum of its parts.’5 In this axis of thinking, things contain multitudes.

Access

The notion of ‘access’ to things is also central to the deep ecology philosophy, defined by Norwegian Ecologist, Arne Naess. Opposed to a mechanistic, hierarchical value system of human and non-human beings, deep ecology states that: 'the presence of inherent value in a natural object is independent of any awareness, interest or appreciation of it by any conscious being'6. Alongside things existing at different scales, there is ‘no intrinsic superiority of human ways of accessing the thing’7. Ecological awareness, to a degree, means self-awareness, as well as re-configuring ideas surrounding the ‘self’. It requires an awareness that a thing exists beyond our own interpretation or experience of it. In a rejection of anthropocentric correlationism, we don’t see things in themselves, but we can see ‘human-flavored correlates’8 of the things. In the realm of illustration, a seemingly objective botanical study of a daffodil suddenly becomes an entangled combination of daffodil + illustrator = illustrator-flavoured-daffodil-picture.

This Object-Oriented Ontology9 establishes that things exist in a profoundly withdrawn way. The closer you look and the more you find out, the further the thing withdraws and the more you realise you don’t know. No mode of access by any being, including itself, can truly show all the qualities and features of a thing. It remains open. Looking at a flower doesn’t tell you its scent, sniffing a flower doesn’t tell you its texture, feeling the petals doesn’t reveal the flavour, tasting it doesn’t reveal much at all (and let’s hope it was edible). Ecological awareness doesn’t mean attempting to understand the thing fully, as an entangled entity, it means acknowledging that you can’t understand the thing fully. It is too complex. It is too strange. There is a ‘mysterious and magical’10 quality when experiencing the world in this way because there are delicious secrets, withheld information, ambiguous influence, twists and loops.

Thanks for reading! Continued next week in Part Two…

Dillard, A. (1975) Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. London: Pan Books Ltd

Morton, T. (2016) Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press

p. 22

p. 25

p. 12

Naess, A. (1986) The Deep Ecology Movement.

Morton, T. (2016) Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 18

p. 29

Harman, G. (2018) Object-Oriented Ontology. UK: Penguin Random House

Morton, T. (2016) Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 17

Great insight & appreciate the references too ... lots of further reading to be had!