John Clare, I hunted curious flowers…

the varied colours in flat spreading fields checkered with closes of different tinted grains like the colors in a map the copper tinted colors of clover in blossom the sun tand green of the ripening hay the lighter hues of wheat & barley intermixd with the sunny glare of the yellow charlock & the sunset imitation of the scarlet head aches with the blue corn bottles crowding their splendid colors in large sheets over the land & troubling the cornfields with destroying beauty.

I hunted curious flowers…

I recently finished reading Olivia Laing’s latest book/collection of essays, The Garden Against Time, In Search of a Common Paradise. The book follow’s Laing’s recovery and restoration of a walled garden in Suffolk, originally designed and cultivated by Mark Rumary. The practical work of uncovering the garden is considered alongside an investigation into the ideas of Paradise, real and imagined, conceived and unearthed, communal and corrupt. It’s a really wonderful bit of writing that points to case studies that explore how humans create and exclude others from beauty, peace, refuge and nature.

Paradise haunts gardens, and some gardens are paradises.

Derek Jarman1

Laing points to ‘the peasant poet of Northamptonshire’ John Clare as someone else caught in a search for paradise. Clare was born in 1793 in an agricultural household, right around the time of the introduction of the Parliamentary Inclosure Acts. These acts formalised and legalised the ‘enclosure’ of what was open, accessible, common land and turning it into private property. Clare’s early writing was celebratory of the surrounding countryside, caught up in the abundance that was available to him. As he got older, his writing becomes more sorrowful and mournful at what has been disrupted and taken away.

The tone of Clare’s early writing has this knotty, intermingling quality that I really love (and feels a bit like Bea’s wonderful writing for our Piece of Turf project). Laing describes this uncultivated approach: “Clare didn’t see nature as a shapeless mass and nor was he interested in discovering a lordly, sweeping, organising view. His preferred way of looking was belly-down in the grass, so that he could swim entranced into a microscopically detailed, teeming world”2.

Much like Donna Haraway’s proposition of Making Kin, Clare’s sense of the world noticed that, “Kin is an assembling sort of word. All critters share a common ‘flesh’, laterally, semiotically, and genealogically. Ancestors turn out to be very interesting strangers: kin are unfamiliar, uncanny, haunting, active…”3

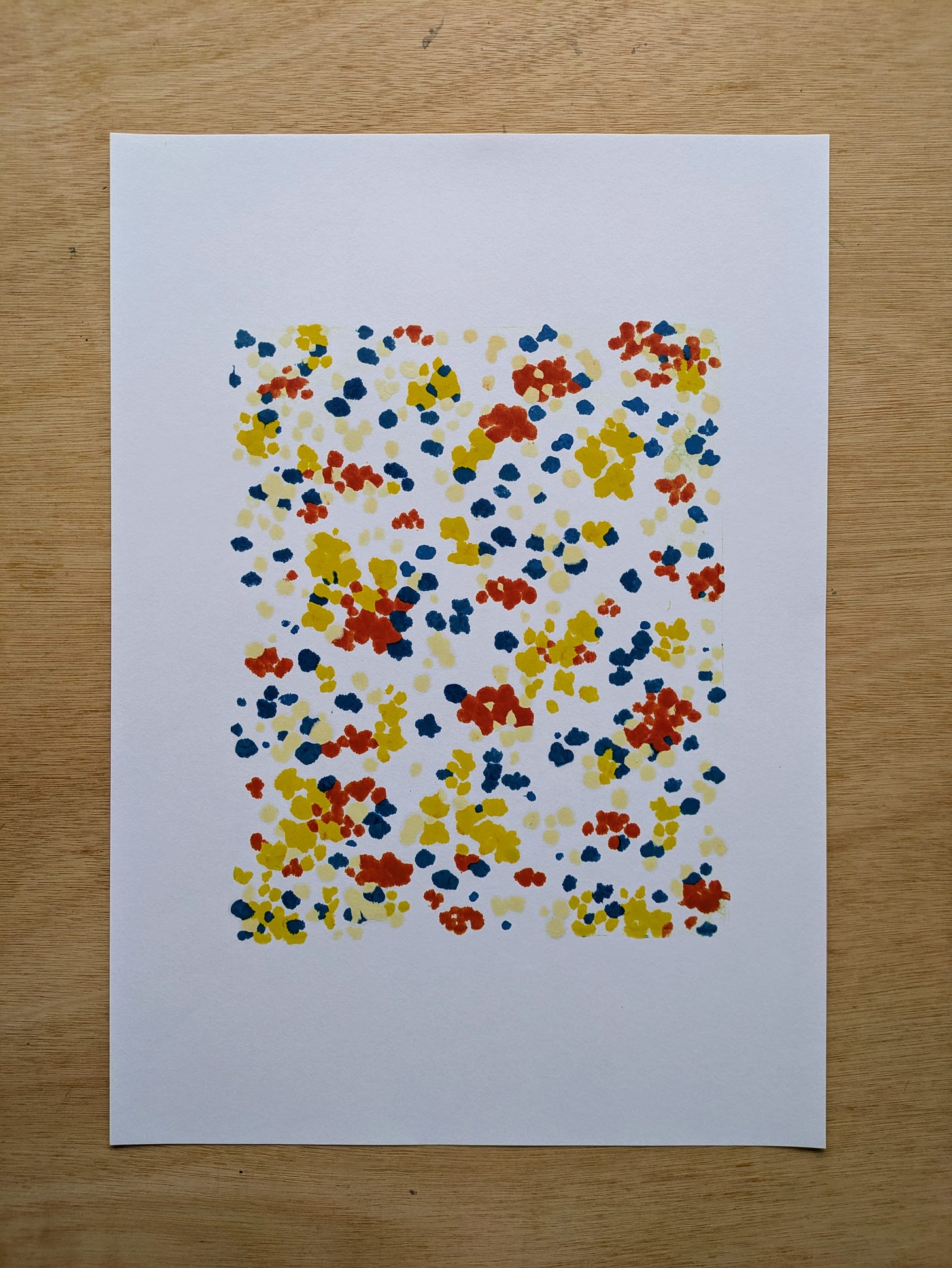

I’d like to get more familiar with Clare’s writing, but I wanted to capture something informed by the extract at the top of this post. It’s interesting to think about agricultural crops of wheat and barley being interlaced with wildflowers throughout (whilst there is a move towards the benefits of biodiverse and regenerative farming practices, it’s still much more common to see monocultural fields of single crops). It feels like an odd symmetry with Clare’s life seen as whole. Someone who grew up in amongst the weeds, but found himself steadily unmoored by systems of power, efficiency and industry. I wanted to make something that felt like being both above and belly-down in the grass at the same time.

With regards to the specific flowers, my interpretation of the dialect is: by ‘yellow charlock’ he’s probably referring to field mustard (Rhamphospermum arvense), ‘scarlet head aches’ are likely to be some sort of hawkweed (Hieracium pilosella) and ‘blue corn bottles’ are almost certainly cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus).

Process

I’m on a bit of a Gelli printing kick at the moment, so the lead image is made up of an assemblage of a few individual prints. They each start with a loose sketch, which is then sat underneath the gel plate as a rough guide, ink painted directly onto the plate and the image then transferred onto paper. (I might do a more in-depth post on this in the future). Whilst I used the first prints for the lead image, there’s something in the second (ghost) prints that I still like and wanted to share here.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

Part of The Goose and The Common, an anonymous, 18th Century poem4

Jarman, D. (1995) Derek Jarman’s Garden. Thames & Hudson: London (p.40)

Laing, O. (2024) The Garden Against Time. Picador: London (p.87)

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying With the Trouble. Duke University Press: New York (p.103)