The following is taken from a presentation delivered in 2022 at ICON11 titled Twists and Loops: Illustrating Ecologically.. The aim of the talk was to reflect on the inputs and development of A Piece of Turf, a collection of drawings and prints produced in response to observations of a small patch of weeds. This work was brought together into a publication and exhibition alongside prose by Beatrice Karol.

You can return to the beginning of this thread here.

Pieces of Turf

Having established some principles of ecological complexity, and ecological awareness, I want to explore how illustration might be able to respond1 to these ideas. If we recognise that, ‘...the world is actual and fringed, pierced here and there, and through and through, with the toothed conditions of time and the mysterious, coiled spring of death.’2 how do we communicate that in a non-reductive manner?

Firstly, I want to take a sidestep for a moment with this painting by Albrecht Dürer, Das große Rasenstück (The Great Piece of Turf) from 1503. This image was a study towards larger paintings, but captures a lot of the essence of my interests here.

Like Dillard’s evocative observations, Dürer’s painting bristles with specificity. What we see is a slice of living, chaotic, complex undergrowth; dandelions, daisies, meadow grass, plantain and yarrow falling into one another and vying for space. We even see glimmers of root systems (perhaps the earth was scooped away to reveal the inner-workings) and the overlaps, overlays and transparencies imply movement, time, ebb and flow. There is no archetypal approach here; this is a specific observation of a particular patch of ground, at a certain time of day.

There is plenty going on here that is ecologically aware. The scale of the observation draws us, literally, into the weeds, into the parts and the details - which are clearly more than the ‘whole’ in this case. The point of access is low to the ground, hunched over, bent double, perhaps more akin to the way a small mammal might approach this particular patch. There is a literal sense of interconnection in the overlaps and overlays and an implied sense of relationships in the bustle of forms, crowded into a small space. Let’s not forget, as well, that we are looking at an insignificant patch of weeds, at best an irritant to gardeners but more likely just overlooked and ignored. It takes an acknowledgement of non-human value to pay attention, look closely and dare to paint something so immaterial.

Unlike ecological awareness however, Dürer’s belief was that this specificity was a reflection of divinity and this process of representation was, in-fact, a means of getting close to God’s perfection in nature. He was seeing nature and seeing God. But, as Morton would put it, this ‘...doesn’t mean you’re ‘seeing’ nature, you are still interpreting it with human tools and a human’s touch.’3 Like Dillard, Dürer’s painting shows a profound connection developed over time and experience and a willingness to impress himself with the full force of the details of his observations.

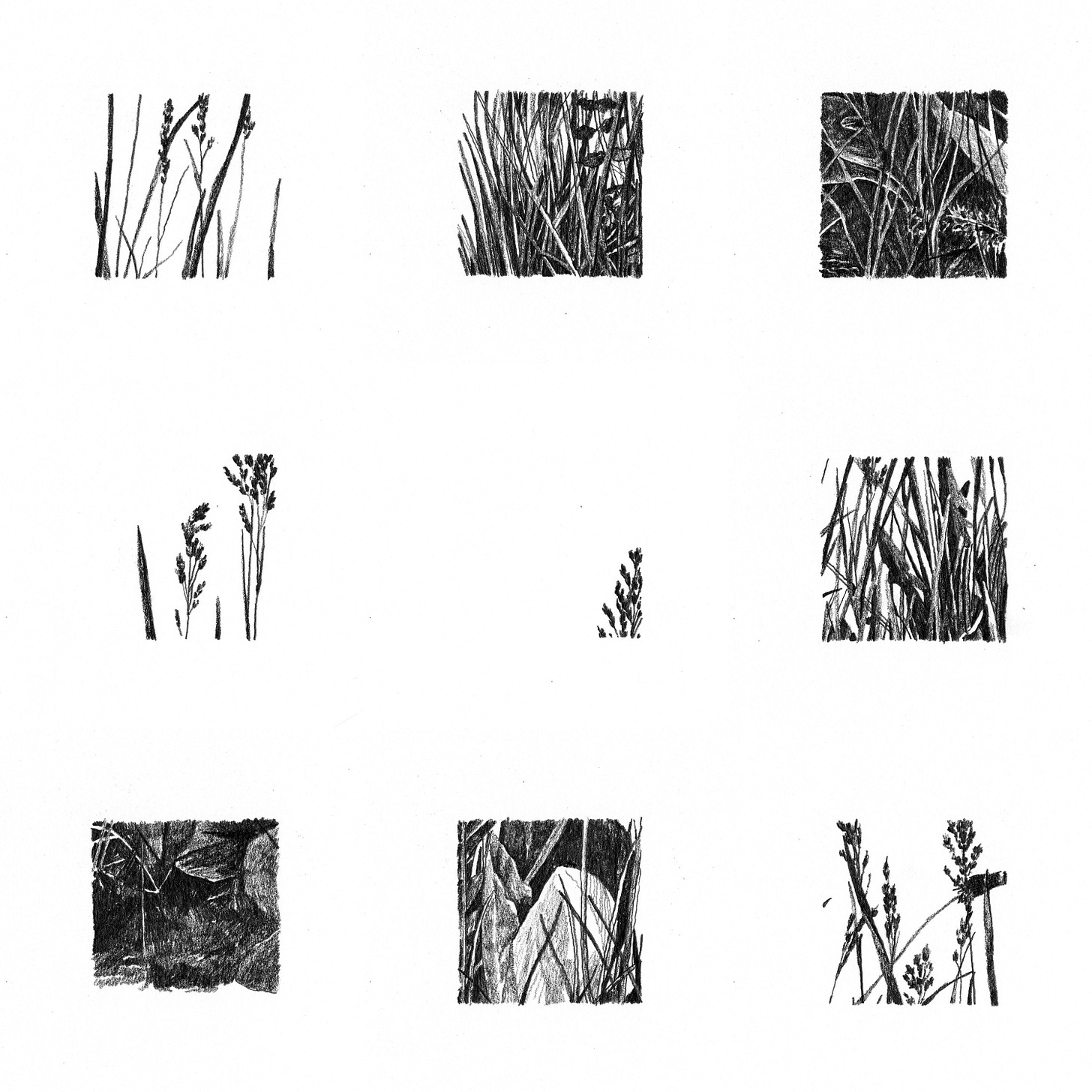

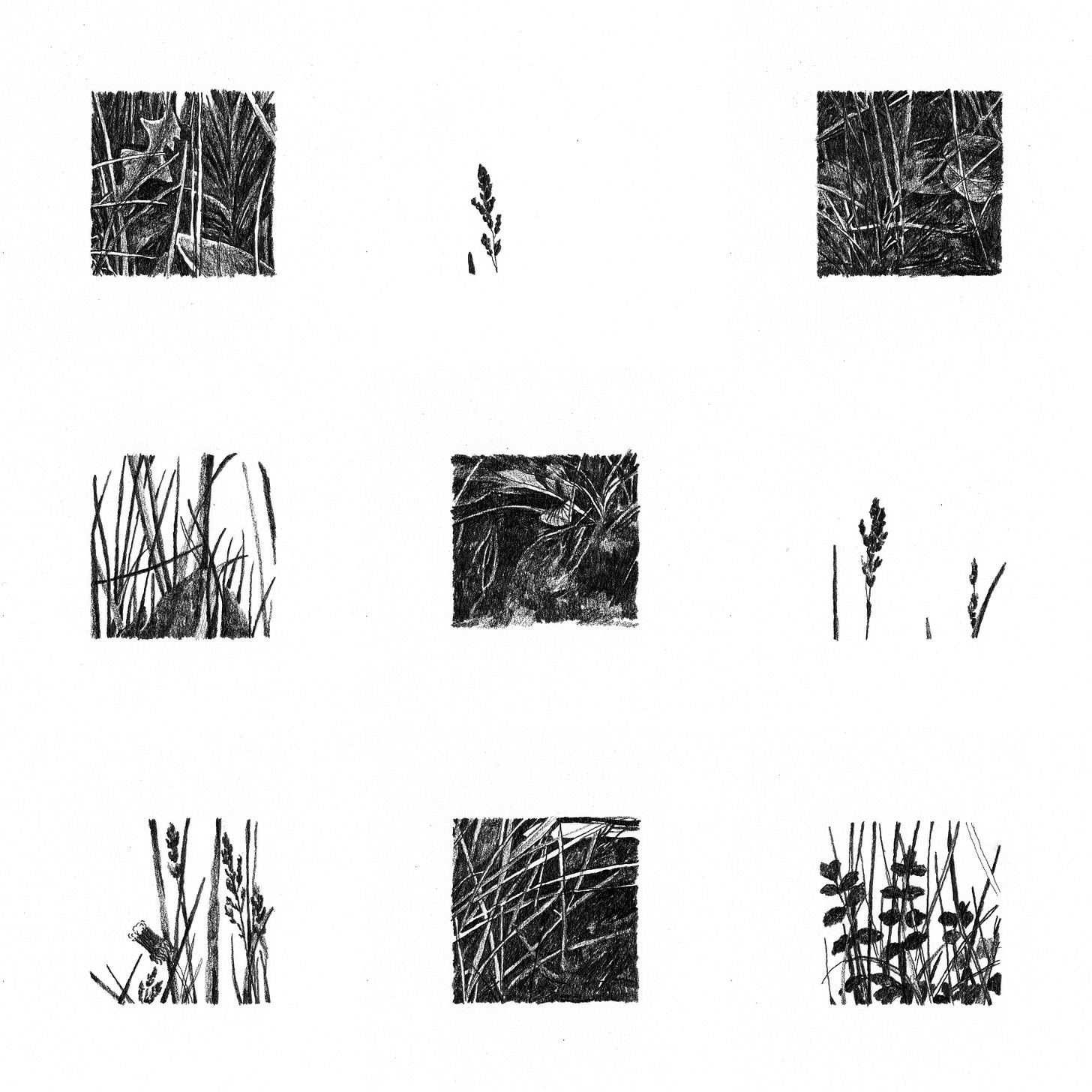

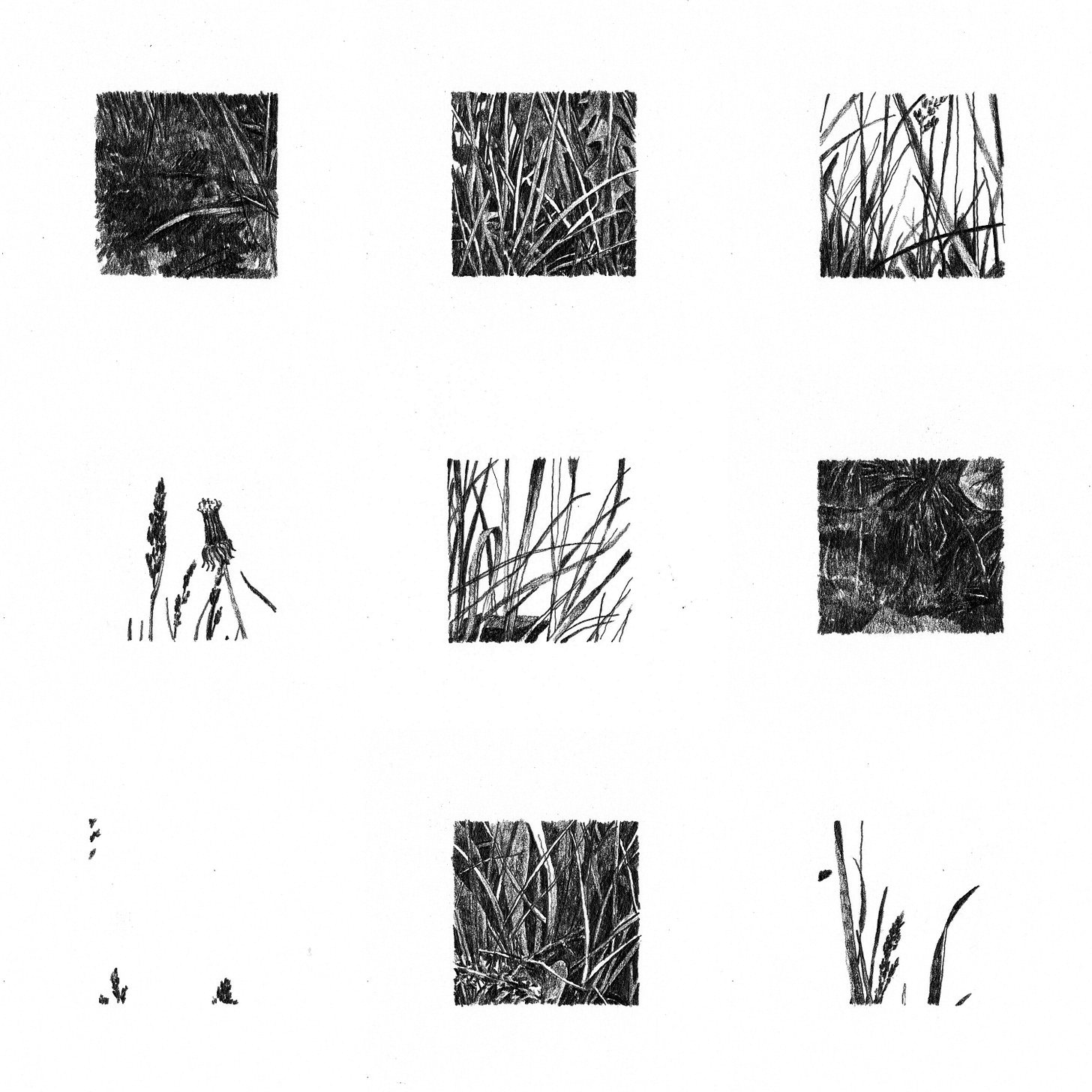

These are drawings made in response to Dürer’s Das große Rasenstück. I am interested in exploring the idea of ecological complexity through the language of drawing and observation. These drawings are made from zoomed in sections of Dürer’s work. Is there more detail to be found in the details? How much can I further explore the idea of scale, access, loops and strangeness discussed previously?

Thanks for reading! Continued next week in Part Four…

Twist

Dillard, A. (1975) Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. London: Pan Books Ltd. p. 206

Morton, T. (2018) Being Ecological. UK: Penguin Random House. p. 27